Liquidation preferences

What are liquidation preferences?

When a private company experiences a liquidity event, such as being acquired in an M&A transaction or winding down, shareholders are typically paid for their equity holdings, such as common and preferred stock.

The rights and preferences of different share classes can vary significantly and are affected by the following rights/preferences:

Original issue price

When a company exits, preferred shareholders must be paid out before common shareholders according to their place in the liquidation stack. For example, VCs are typically paid out before employees.

The original issue price (OIP) is the price at which investors purchased preferred shares. Under standard terms, the “liquidation preference = OIP * No. of Outstanding Preferred Shares.”

Investors will convert their preferred shares to common shares when more advantageous. For example, imagine a preferred shareholder has a $5 million liquidation preference. They can either receive their total liquidation preference ($5 million) or convert their preferred shares into common shares, receiving a total payout greater than $5 million.

Liquidation preference

As mentioned earlier, a preferred shareholder’s liquidation preference is typically paid out first. Share class seniority determines which share classes get paid out first.

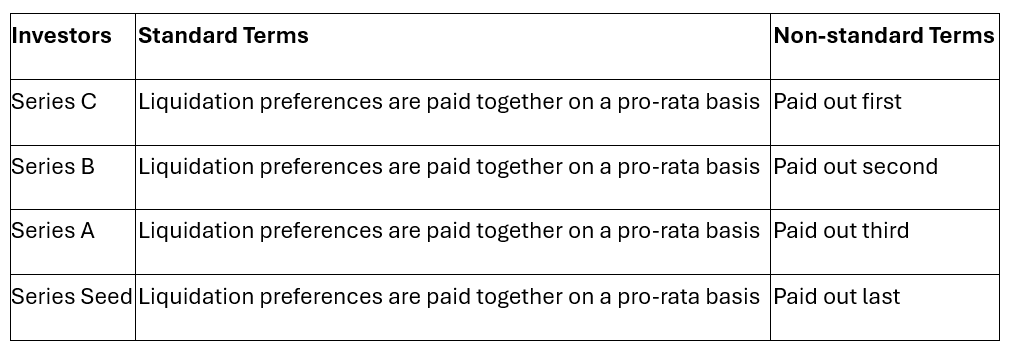

For example, let’s say a Series C company exits via an acquisition might look like this:

In contrast to the “Standard Terms” above, non-standard terms (often called “stacked”) preferences occur when later-stage investors negotiate the ability to be paid out before earlier-stage investors. Investors holding preferred shares with stacked preferences have added protection against downside exit scenarios.

When a company’s exit valuation is less than the combined investment by preferred shareholders, common shareholders receive no payout. Secondary buyers of common shares should be acutely aware of this scenario. In short, a company can– on a headline basis – achieve a strong exit, but a common shareholder can be left with nothing by the time the “pref stack” has been paid out.

Liquidation multiplier

An example of a non-standard term is preferred shareholders' “liquidation multiplier.” These terms allow investors to receive a “multiple” of their liquidation preference before choosing to convert their preferred shares into common shares.

Like stacked preferences above, liquidation multipliers give investors even more protection against a company’s downside exit scenarios at the expense of other equity holders.

In simple terms, imagine a Series B investor with an OIP of $5 and a 2x liquidation multiplier; their liquidity preference would be worth $10m. If the company ultimately exited for only $10m, common shareholders would receive nothing.

Cumulative dividends

Because dividends in technology startups are normally not paid out regularly, the buildup of cumulative dividends is like interest on debt. For preferred shares, dividends are designated as either cumulative or non-cumulative.

Cumulative dividends are earned and accrued over time, whether or not the board declares it. However, cumulative dividends are typically only payable if and when declared by the board.

Non-cumulative dividends are declared and paid out only at the board's discretion. They do not accrue to shareholders in the way that cumulative dividends do.

Typically, cumulative dividends accrue from the shares’ issue date until the company exits. Any accrued dividends are added to the investor’s liquidation preference upon the company’s exit.

For example, let’s assume an investor purchases one million Series A preferred shares with an OIP of $5.00. The shares also have a non-compounding cumulative dividend right of 5%. If the company were to exit in five years, the investor would be owed the liquidation preference of $5 million and $1.25 million of accrued dividends.

Conversion ratio

Preferred shareholders will elect to convert their preferred shares into common shares if it would result in a payout greater than the preferred shares’ total liquidation preference.

So far, we have assumed a one-to-one conversion ratio of preferred to common shares, making the calculation easy.

However, this conversion ratio can differ; for example, it could be four-to-one. In this scenario, an investor would convert their preferred shares into 4 million common shares if the payout for a single common share was at least $0.25. Because investors receive 4x the number of common shares upon exit under this conversion ratio, they would convert at a lower value of common shares.

This conversion ratio allows investors to participate in a greater percentage of a company’s future payout. With a one-to-one conversion ratio, investors would participate in 50% of total distributions. However, with a four-to-one conversion ratio, investors would participate in 80% of total distributions.

Participating preferred

Participating preferred stock gives preferred shareholders an economic benefit that allows them to receive additional proceeds—on top of their liquidation preference—before converting their preferred shares into common shares and participating in the remaining proceeds (on a pro-rata basis) alongside common shareholders.

For example, preferred shareholders with participating preferred rights could commit $5 million and own 20% of the company. If the company subsequently sells for $10 million, the investor will receive $5m (liquidation preference) plus another $1m (20% x $5m).

Sometimes, participating preferred sticks have capped participation rights, and investors only participate in the “remaining proceeds” with common stockholders until they reach their cap, which is typically a multiple of their liquidation preference.

Concluding words

As a direct secondary investor, it is extremely important to model a company’s share class structure and model exit scenarios at different valuations. Nodem builds an additional margin of safety by constructing well-diversified portfolios.

Interested in more educational content? Read about preferred equity here.